Artist of the Month > 2022 Artists

ARTIST PROFILE

NAME: Ross Morin

LOCATION: Mystic, Connecticut

ORIGIN: Maine

ART: Writer, Director, Editor, Sound Designer, Cinematographer, Producer

MAIN GENRE: Horror and Documentary

TRAINING: Master of Fine Arts in Film and Video Production from Ohio University in 2008

ARTS AFFILIATIONS: The Artists Forum

BIO: Ross Morin is an award-winning filmmaker, screenwriter, cinematographer, and editor. He is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Film Studies at Connecticut College where he teaches filmmaking. As a queer filmmaker, he challenges ideas of traditional “straightness” and masculinity through his work, usually in the horror or drama genres. His works include the award-winning films: A Wheel out of Kilter (2015), A Peculiar Thud (2016), In a Landscape Dreaming (2019), and many others.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS: Ross Morin is the recipient of the University Film and Video Association’s Award of Teaching Excellence for Senior Faculty; Connecticut College’s highest teaching honor, the John S. King Memorial Teaching Award; Ohio University’s Graduate Associate Outstanding Teaching Award; and the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Faculty Mentor Award.

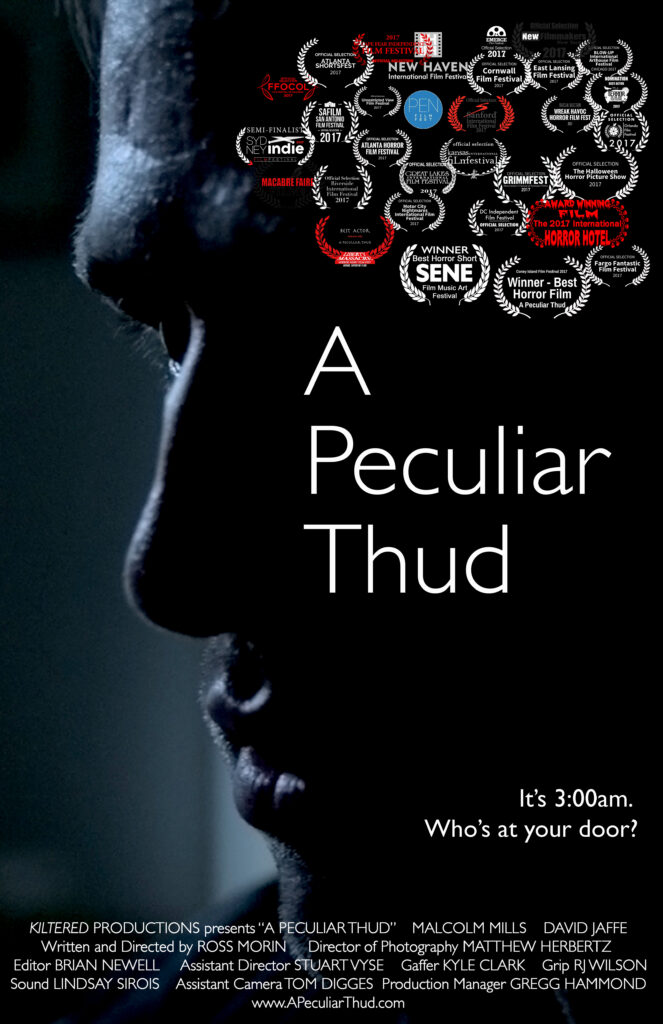

His feature film, A Wheel out of Kilter (2015), won the Indie Spirit Award at the Princeton Independent Film Festival and Best Feature Film at the Macabre Faire Film Festival. His film, A Peculiar Thud (2016), was the official selection of over 30 film festivals around the world and won the Best Horror award at the Coney Island Film Festival and the Best Horror Short at the Southeast New England Film.

His film, In a Landscape, Dreaming (2019), won Best Foreign Film at the Pune Short Film Festival in India, and Best Music Video at The Artists Forum Festival of the Moving Image: 2019 in NYC. His most recent film, ¡Come! (Eat!) (2019), is currently streaming on HBO Max.

LATEST WORKS: Ross served as producer, assistant director, and editor for Brian Newell’s Hide or Seek (2021), made with his friend and collaborator – writer/director Brian Newell. This fall, he will have a chapter in the first edited volume of essays about Tommy Wiseau’s The Room. His chapter is called, “The Room in the Classroom: How I Use a Bad Movie to Teach Good Filmmaking.”

WORK SAMPLES: Two short films: In A Landscape, Dreaming, and A Peculiar Thud. Two Trailers: A Wheel out of Kilter and Hide and Seek.

INTERVIEW

Please describe your artistic themes

My work is driven by the need to challenge pervading ideologies and point to ways that we can be better citizens of a diverse and global society. My films take strong humanistic stances from sociopolitical, psychological and philosophical perspectives. In particular, most of my films deal with issues of gender anxiety and the crisis of masculinity that leads to violence and hate in our culture. I believe that gay bashing, spousal abuse, bar fights and even war are helpfully understood as manifestations of insecurities about maleness and masculinity.

As an openly gay man who grew up in the 80’s and 90’s, I am no stranger to anxieties about masculinity that can lead to physical and psychological pain and trauma. My work sets out to highlight this problem by showing characters who reject traditional ideologies of masculinity and gender to find peace and happiness. It is important to me that I use the medium with purpose as I tell compelling stories.

I view filmmaking equally as forms of art, intellectual engagement, and entertainment. My philosophy leads me to produce different types of films from those by more mainstream filmmakers whose primary goal is to entertain the audience. I try to make work that is “intellectual” in nature by infusing it with my knowledge of film history, theory and philosophy, facilitating the exploration of a variety of topics in the field of film studies.

I try consciously to draw from and contribute to a history of work in my field, relating my films to past and present artistic and theoretical works in ways similar to how scholars in other fields draw from and continue the work of scholars before them. One of my goals, as I move forward in my career as a progressive independent filmmaker, is to make films that are fun and accessible to wider audiences and still contain a set of philosophical and psychological ideas that have motivated me as an artist for years.

Please describe your creative process

It’s a case of an idea finding its way into my consciousness, where it will stay lodged for a while, competing with other ideas.

I get probably 30 different ideas for a new movie every week. Since I make about a movie a year, that means about 1 out of every 1,500 ideas ever sees the light of day (or light of a projector). I would say that each of my 50 or so movies has always begun with a visceral gut feeling. Working in horror, for me that has meant that I start with a feeling that makes me absolutely tense, short of breath, even, literally, “tingly.” These feelings are almost always caused by a fragment of an idea – an image, a line of dialogue, a situation, an edit, or a music cue.

My artistic process is to rather passively, but mindfully, let those fragments, and the visceral bodily responses that accompany them, fester and develop in my subconscious. I let them fester for days, weeks, months, or even years sometimes. Most of the time, the feelings wane quickly. But the feelings that stick around, or even grow stronger – those are the ones I decide to pursue. Often, if the feelings grow, the ideas surrounding them tend to develop, too. So not only am I feeling stronger, but the world of the story is growing more vivid, too. I start to see characters, locations, relationships; I start to see story structure and plot.

If I feel that my visceral responses to my developing ideas are really taking root, then I move forward. This point is far more selective; very few ideas make it this far for me. If a film makes it to this point in my process, I’d guess about 1 out of 3 will actually turn into a film.

From there, I actively and rigorously outline and world-build. I journal, I visit locations that feel like where the film would take place, I put myself into the psychological positions of my characters, and I just immerse myself in the world of the film. I “test” the film to see if it seems worthy. If it makes it past the scrutiny, then I write a draft of a script and share it with my closest filmmaking collaborators. If their feedback is enthusiastic, I consider it a green light. Then the real writing process begins.

What are your artistic goals? What do you need to achieve them?

My artistic goals are to continue collaborating with like-minded, hard-working, and fun-loving people on films until I’m physically or psychically unable. I have found, time and time again, that it is the process of collaborating with others on work that is mutually meaningful that makes me feel most alive and joyful.

When my films receive any recognition, my first thought is: maybe this will help me meet more great people with whom I can work on the next project. I don’t really aspire to more money (though I wouldn’t turn it down), or fame (I’m a private person), or recognition (the good feelings fade awfully quickly). I count my success as an artist by the friendships and relationships I’ve made along the way. All I need, I suppose, are good, hard-working, thoughtful people- and I am so grateful to have so many in my life already.

What are your views on the industry?

There are so many industries, it’s hard to begin to answer this question without defining our terms. My Connecticut College colleague, Dr. Nina Martin, could far better unpack this than me… I suppose if I think of “the industry” as a concept wherein moving image media is very well-funded, very integrated with talented resources of cast and crew, and very available for public consumption, then I would say my feelings are mixed. One the one hand, I acknowledge, accept, and am saddened by the racism, sexism, homophobia, nationalism, ageism, ableism, and countless other oppressive and bigoted “isms” that have been a part of the industry since its inception. On the other hand, I am grateful that the industry is able to acknowledge its social and moral responsibilities and integrate a commitment to inclusive values through various hiring and content-driven initiatives.

It is increasingly difficult to condemn the industry as obviously and unambiguously evil. While “socially-conscious” hiring and content initiatives may be driven by money, fear of being “canceled,” or other ego-oriented benefits; and while they have sometimes resulted in more bigoted mis-steps than if they hadn’t tried at all; and while their actual positive impacts have only begun to appear (and in such small, small doses) – I do feel optimistic knowing that young people today are seeing representations in front of – and behind – the camera that I never saw when I was a kid.

As a gay kid in the 1980s and 1990s, I never saw a same sex kiss on TV, and there was no way to seek out such representation. I appreciate and respect that now, while there is still far, far, too little representation outside of white middle class cis/heteronormativity – it exists. And that means something. So – yeah… my feelings on the industry are mixed.

I’ll also note that I have many friends and former students who have careers in the industry as sound recordists, lighting techs, set decorators, production assistants, etc., outside the (absurdly) glamorized job of being a writer/director “auteur.” I grew up working as a roofer for my father (who also was a full time firefighter for the city), and I gained a sense of the value of an industry that creates and provides jobs and income for people who have no interest in being in the spotlight.

Once again I am of two minds. I know people who are in unions and working steadily, and seem to feel that they are part of an industry that supports them. But I know far more who have taught me that this industry is often more heartbreaking as many jobs are temporary, gig-to-gig, and so much talent is underutilized and unseen.

I know of so many people who have chosen to leave their homes, families, and friends, to move across the country only to spend half a year trying to get a job, and even if they succeed, the job ends, and they are unemployed once again. The gig-driven and exclusive moving image industry is so unique compared to, say, the roofing or firefighting “industries” particularly because of the amount of heartbreak and dream crushing it often brings to those who are willing to give it so much. I think the moving image industry represents the brightest capitalist American dreams at the same time it manifests the darkest capitalist American nightmares.

What advice would you give to emerging artists?

Don’t wait until it’s perfect. Make the movie. If I am in some way even mildly successful as an independent film artist, it’s because of the dozens of movies I made when I was younger. I was not naturally talented as an artist or filmmaker; I learned by doing. In every movie you make, no matter how many you’ve made, you learn a thousand things. If you wait until the script is “perfect,” you’ll never make it (because the script will never actually be perfect no matter how many drafts you write), and you’ll miss out on opportunities to grow.

Be humble about the process of learning. Make films with the additional goal of learning. Never go into a film thinking you know all there is to know. A lack of humility is a lack of a will to learn. Study the liberal arts. Study Philosophy, Psychology, Sociology, History, and so on. How else are you to make a film that is actually about something?

WEBSITE: rossmorinfilm.com

FACEBOOK: @ross.morin

INSTAGRAM: @140mmoftravel

VIMEO: rossmorin